It was in the broad sweep of the Platte Valley, where the prairie rolls gently toward the Sandhills, that the town of Cairo took root. The place first came into being not through a deliberate plan of settlement, but as a necessity of the railroad. In 1886, when the Burlington and Missouri River Railroad pushed its line westward from Grand Island toward Billings, Montana, it followed a pattern common to railroad expansion across the Great Plains: at regular intervals of eight to ten miles, water stops were established for the steam locomotives. These, in turn, became centers of trade and settlement. Many such points later dwindled into ghost towns; others, including Cairo, survived and grew into thriving communities.

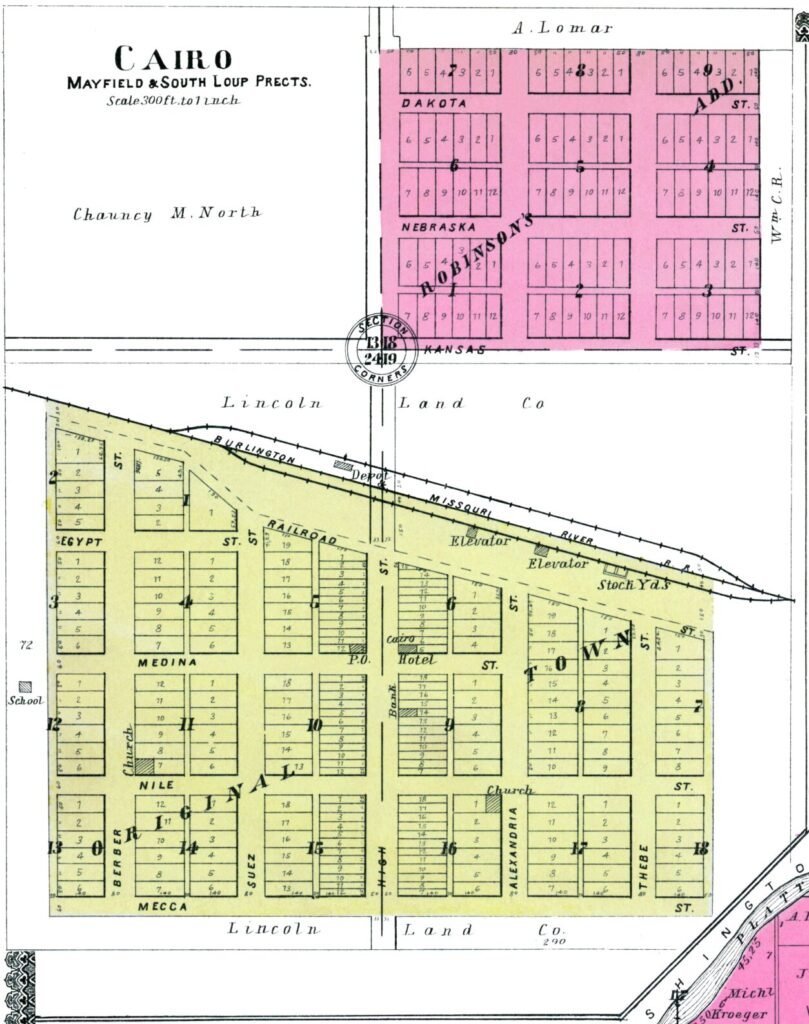

According to tradition, the naming of the town was a lighthearted moment among the surveyors who first laid out the site. Looking across the sandy soil and sparse vegetation, one of the engineers is said to have exclaimed, “It looks like a desert—let’s call it Cairo!” The name, borrowed from the Egyptian capital, fit the arid scene, and the surveyors extended the theme across the town’s plat. Its streets bore the names of Egypt and Arabia: Suez, Mecca, Nile, Alexandria, Berber, Thebe, Medina, Nubia, Said, and Egypt. In time, however, Nebraskans made the name their own, pronouncing it “Karo,” much like the syrup. When members of the Cairo Roots Society compiled Cairo Community Heritage for the town’s centennial in 1986, they noted that no one could say exactly when or why this local pronunciation took hold.

Long before the railroad arrived, settlers had begun to take up land in this part of Hall County. The first pioneers came in 1873, staking homesteads on the open prairie. They were a varied company—farmers from the eastern states, immigrants from Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Ireland, England, and Poland, and even a few Black settlers seeking opportunity on the plains. Their diversity gave Cairo from the outset a character of cultural blending typical of so many Midwestern towns; it was, in the phrase of its chroniclers, a true American “melting pot.” These early settlers endured the privations of frontier life—grasshopper plagues, prairie fires, and drought—but their persistence prepared the way for the town that would soon follow.

The establishment of Cairo as a town came through the Lincoln Land Company, a subsidiary of the Burlington Railroad that handled the development and sale of town sites along the line. The company selected the farm of George Bussell for the Cairo town site in 1886. Bussell and his wife had only recently completed a fine home and, reluctant to give it up, he set what he thought was a prohibitive price—twenty dollars an acre. To his astonishment, the company agreed to pay it. His handsome house, at 205 Suez Street, long remained one of the architectural landmarks of the community.

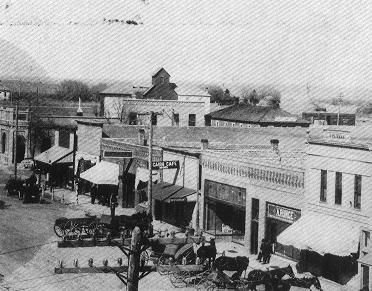

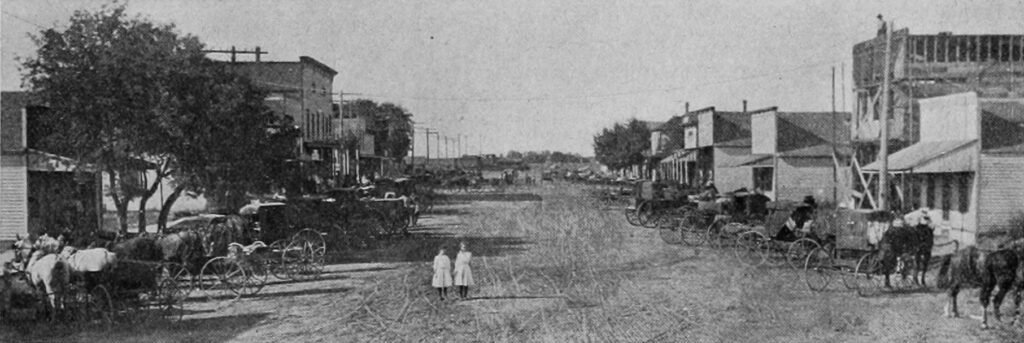

From that beginning, Cairo’s growth was swift. Within a single year, what had been a field of corn became a busy main street lined with stores, shops, and offices. The town boasted a school, three churches, and three cemeteries, and its population reached two hundred. The surrounding farms prospered, and Cairo became a shipping point for grain and livestock as well as a center for local trade.

Among those drawn to the area during its early years was a young Nebraskan whose name would later gain international renown in the world of art. Solon Borglum, son of an Omaha physician and brother of Gutzon Borglum—famed sculptor of Mount Rushmore—came to manage his father’s ranch near Cairo in the late 1880s. In his spare time, Solon carved large faces into the nearby bluffs, visible from the road as late as 1906. Inspired by his brother, he pursued formal study in Paris, where he earned the title “le sculpteur de la prairie” for his depictions of the cowboys, horses, and Native Americans of the western plains that had first inspired him in Nebraska.

In 1889, the town gained another distinction when Chancey North brought seven imported brood mares and a stallion to Cairo, forming a partnership with William Robinson to establish “North & Robinson,” a livery and breeding enterprise. Their fine Belgian horses were in great demand across the region. The firm’s success led them in 1895 to organize the first livestock company in nearby Grand Island. The silhouette of the Black Stallion that once topped their Cairo barn became a familiar emblem of quality stock, and a similar figure still adorns the Third City Sale Barn in Grand Island.

By the turn of the century, Cairo’s commercial and social life was well established. Dell Thompson erected an opera house, providing a venue for performances, lectures, and public gatherings. The town also supported a race track, a brick factory, a flour mill, and a municipal band, as well as a sprinkler wagon to keep down the dust on its unpaved streets. Merchants from Grand Island, recognizing the vitality of the young town, extended their businesses into Cairo. It was, as residents liked to say, “bound to boom.”

Through the decades that followed, Cairo continued a steady, if modest, growth. The census of 1911 recorded 364 residents; by its fiftieth anniversary, the number stood at 400; by 1961, at 500; and at its centennial in 1986, nearly 800. Its fortunes rose and fell with the rhythms of rural Nebraska—good years of crops and high prices alternating with the lean years of drought or depression—but the community endured. Those early railroad towns that had once shared its prospects—Cameron, Ovina, Zurich, Berwick, Easton, Rundelett, Loyola, and Runelsburg—gradually vanished, leaving Cairo among the few survivors of the Burlington’s original water stops in Hall County.

Modern Cairo still honors its past. The “Oasis on the Prairie,” as it styles itself, lies at the junction of Highways 2 and 11, where the coal trains of the Burlington Northern now pass through without pausing at the old depot. Its school has joined with those of Boelus and Dannebrog to form the Centura School District 100, and the town continues to balance progress with pride in its heritage. The community logo—an image of pioneers framed by a broken ear of corn—represents both continuity and hope: a continuity of the golden past and a hope for the future, rooted in the bounty and beauty of the Nebraskan plains.

Source

Partridge, Dennis N., “A History of Cairo, Hall County, Nebraska.” Nebraska Genealogy. September 27, 2025.

Back to: Nebraska Community Histories

Discover more from Nebraska Genealogy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.